How Dr. King Defined Justice: Collective Liberation

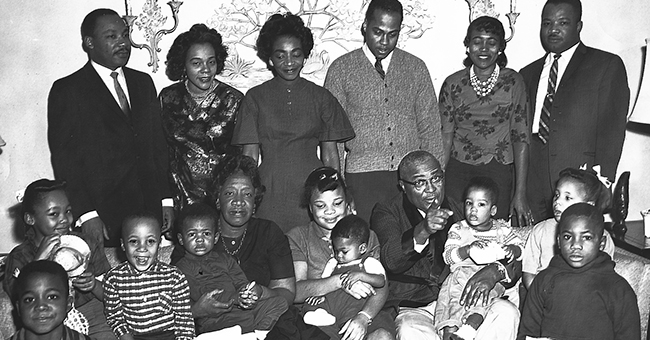

(photo credit: Bruce Davidson)

By Justin Marschke, Creative Manager at Beneficial State Foundation

“We the People” have long struggled to agree on the meaning of justice. Some believe it belongs to a few, while others insist it belongs to us all. As we commemorate the life and legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., we are invited to expand our vision of justice through the perspective he embodied, shaped by lifelong learning and organizing across diverse movements that demanded freedom for all oppressed people.

“We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

—King, Letter from a Birmingham Jail (April 16, 1963)

For many of us, studying Dr. King beyond the limits of our K-12 curriculum revealed how his words have often been distorted and used against the very causes he championed. Decontextualized quotations, misappropriation, and co-optation have obscured the depth, rigor, and urgency of his teachings. Especially in an age of (mis)information, it is crucial to study him holistically not only for historical accuracy, but also for understanding the ethical and strategic principles he offered for confronting injustice. This piece carefully approaches Dr. King’s teachings, bringing them into conversation with contemporary lenses rooted in his legacy and the broader lineage of collective liberation. It explores how he defined justice and invites reflection on how we all can continue the work today.

King devoted his life to justice as a collective pursuit. He built diverse, cross-class solidarity through a movement that sharpened public understanding of systemic oppression and how to dismantle it. Ahead of his time, he faced intense targeting and hostility for disrupting the inhumane status quo. In an internal FBI memo, he was called the “most dangerous and effective Negro leader in the country.” Yet his legacy continues to inform people and policies toward a more just society for all.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

—King, Letter from a Birmingham Jail (April 16, 1963)

Dr. King recognized racial injustice, economic injustice, and militarism as inseparable forms of structural violence—each reinforcing the others. He identified how racial division was deliberately constructed by the ruling class to fracture working-class solidarity and extract wealth and resources from the global majority. This understanding shaped how he mobilized mass movements to confront these interlocking conditions of exploitation.

Nonviolence is a timeless tradition practiced across centuries and cultures. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change (The King Center) defines it as “a love-centered way of thinking, speaking, acting, and engaging that leads to personal, cultural and societal transformation.” As described in his first book, Stride Toward Freedom, the tenets of Dr. King’s philosophy of nonviolence outline principles and steps for social and interpersonal change.

Unfortunately, King’s approach has often been caricatured as a reductive form of pacifism that categorically rejects all forms of self-defense. In actuality, he affirmed self-defense as morally understandable, while distinguishing it from violence deployed as a primary political strategy. This distinction is crucial. He cautioned that retributive violence is ultimately an ineffective strategy for peace and justice because it perpetuates cycles of revenge, corroding moral conscience through endless retaliation. In a society structured by white supremacy, King observed that riots intensified white fear while relieving white guilt without advancing justice. At the same time, he insisted that it would be morally irresponsible to condemn rioting without also condemning the intolerable social conditions that leave people feeling they have no other alternative.

King articulated this tension clearly when he said:

“A riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the negro poor has worsened over the last twelve or fifteen years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice and humanity.”

—King, “The Other America,” Grosse Pointe High School (March 14, 1968)

With compassion for those driven to riot, Dr. King encouraged community organizing and strategic mass demonstrations of nonviolence as an effective means to generate systemic change—as well as a comparatively safer strategy for pursuing justice. He did not moralize violent rebellion but cautioned that it reinforces cycles of retribution. By breaking these cycles, nonviolence opens pathways toward reconciliation and substantive peace. It advances justice by loosening society’s clench around the recursive loop of violence that sustains oppression.

Nonviolence calls for practice, not perfection. It is cultivated in our hearts and minds, then refined in our relationships and communities. It is embodied in our actions before taking shape in our systems. Without this practice, violence may be a tempting yet ultimately self-defeating strategy:

“The ultimate weakness of violence is that it is a descending spiral, begetting the very thing it seeks to destroy. Instead of diminishing evil, it multiplies it. Through violence you may murder the liar, but cannot murder the lie, nor establish the truth. Through violence you may murder the hater, but you do not murder hate. In fact, violence merely increases hate… Returning violence for violence multiplies violence, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that.”

—King, cited by Center on Conscience and War, from Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967)

Especially when we feel righteous indignation, nonviolence invites a grounded perspective that expands our choices and helps us avoid becoming the injustice we oppose. When we inevitably encounter disagreement or conflict, nonviolent practice calls us to remember the difference between an opponent and an enemy: an opponent may want to prevail, but an enemy wants someone to suffer. An opponent remains oriented toward a fair outcome, while an enemy perpetuates the descending spiral of violence. When we remain rooted in our humanity, nonviolent communication and action enable us to engage conflict with tact and integrity. Dr. King exemplified this through what he called creative dissent:

“Let us be those creative dissenters who will call our beloved nation to a higher destiny, to a new plateau of compassion, to a more noble expression of humanness.”

—King, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967)

Justice is not accomplished through a zero-sum mindset, nor does it demand retribution. This misconception underlies divisive political strategies, including reactionary backlash to efforts addressing systemic inequality. Justice demands accountability, repair, and an end to unchecked abusive power and cruelty. It lays groundwork for collective healing—for those harmed and for those who have caused harm. Acknowledging that perpetrators also carry unresolved wounds from violence does not excuse harm; it clarifies how systems reproduce it and where they require repair.

Dr. King named the Three Evils of Society—Racism, Poverty, and Militarism—as the interlocking forms of violence that uphold oppression. King sought to dismantle these evils through direct action grounded in integrity, respect for shared humanity, and reverence for the interrelatedness of all life. By situating forms of exploitation within a global moral framework, his activism helped lay some groundwork for contemporary approaches to climate justice—including attention to the devastating consequences of militarized extraction and ecological destruction. Today, climate justice is widely understood as inseparable from racial and economic justice, encompassing broader systems of power, health, and indigenous sovereignty.

Scholars drawing upon King’s legacy have offered contemporary language and frameworks that further clarify links between Racism, Poverty, and Militarism. For example, bell hooks described the US sociopolitical system as an “imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy” throughout much of her work. In a 1989 paper examining how overlapping systems of bias and violence impact the lives of Black women, Kimberlé Crenshaw introduced the term intersectionality, offering a lens for observing where power comes, collides, interlocks, and intersects across multiple social identities.

The King Center identifies some contemporary examples of each evil to show their systemic scope. Within the category of Racism, these examples include sexism, colonialism, and discrimination against disabled people, among others. In the following quote, notice how King’s description of Racism applies beyond race alone—and how sexism or other forms of discrimination could be substituted without changing the underlying logic of harm:

“Racism is a philosophy based on a contempt for life. It is the arrogant assertion that one race is the center of value and object of devotion, before which other races must kneel in submission. It is the absurd dogma that one race is responsible for all the progress of history and alone can assure the progress of the future. Racism is total estrangement. It separates not only bodies, but minds and spirits. Inevitably, it descends to inflicting spiritual and physical homicide upon the out-group.”

—King, cited by The King Center, from Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967)

On Poverty, King consistently emphasized how economic exploitation functions as violence because it shortens lives, denies basic needs, and persists through policy and neglect. Additionally, people subjected to Poverty are treated with contempt and criminalized for their circumstances. While these interlocking forms of structural violence can affect anyone to varying degrees, many veterans who suffered from serving the machinery of Militarism later face compounded harms of Racism and Poverty, rather than receiving dignity and care after the trauma they endured. Militarism not only normalizes violence against perceived out-groups but also entrenches coercion and dehumanization within social values.

Militarism, both domestically and abroad, has made the US one of the most powerful—yet destructive and feared—nations in the world. History repeatedly shows that power consolidated through violence and intimidation erodes trust and becomes increasingly unsustainable. Resentment, estrangement, and alienation only worsen under constantly coercive conditions. Peace requires intentional efforts to acknowledge harm, pursue repair, and work toward reconciliation.

King, hooks, and Crenshaw’s insights reveal that social crises are not simply individual failures but symptoms of systems designed to normalize inequality and sustain oppression. Too often, structural violence is misrepresented as personal shortcomings, shielding those in power from accountability and reinforcing dominant narratives. The blame and denigration directed at oppressed adults readily serve systems of domination by obscuring structural responsibility. As a result, this framing rarely confronts the reality that children lack full civil and political rights and legally protected avenues for self-advocacy. Instead, these presumptive narratives normalize the subjugation and structural violence inflicted on people who are most vulnerable and least able to resist.

In All About Love: New Visions, bell hooks critiques how these same systems—particularly patriarchy, a system that privileges male domination over women and children—distort human connection and our relationship to the natural world. She illustrates how, within families, oppressive conditioning warps love into coercive, abusive, and deceptive patterns that children carry into adulthood. Insisting that “love and abuse cannot coexist” and that “there can be no love without justice,” hooks frames love as a disciplined, accountable practice rather than a feeling. Akin to King’s framework of nonviolence, she presents love as an essential ethic for freedom from oppression—one that requires ending domination and cultivating care, responsibility, and respect. When rooted in compassion, this practice makes forgiveness, repair, and healing possible as manifestations of redemptive love.

bell hooks draws this deeper meaning of love from many sources, including Dr. King’s teachings on agapē (pronounced “ah-GAH-pay”), which is one of several Greek words that translate to specific forms of love. Agapē is the kind of love King described as an “understanding, creative, redeeming goodwill for all,” “an overflowing love which seeks nothing in return,” and “the love of God operating in the human heart.” At this level, “we rise to the position of loving the person who does the evil deed while hating the deed that the person does.” This love is not to be misconstrued with desire (eros) or fondness (philia). This love is inseparable from justice:

“Agapē is not a weak, passive love. It is love in action. Agapē is love seeking to preserve and create community. It is insistence on community even when one seeks to break it.”

—King, “An Experiment in Love,” A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1958)

These insights reclaim collective agency by restoring our practical capacity to intervene at the root causes of the recursive lovelessness embedded in systems of oppression. While systems shape individual behavior, collective action can reshape systems themselves. Where structural violence degrades humanity’s wellbeing and sense of shared responsibility, nonviolent practice opens pathways of freedom for the oppressed as well as the possibility of redemption for those who have wielded oppressive power—through accountability, reparations, and the relinquishment of unjust power. In this way, Dr. King’s legacy shows that all liberation is inherently intertwined and that mass mobilization is both possible and powerful. Together, we can continue building a global, love-centered movement for collective liberation—one capable of rendering the tools of oppression obsolete.

Long before the normalized cruelty of our current era, Dr. King helped us recognize that “power without love is reckless,” and that love without power cannot confront injustice. Both love and power are essential in the service of justice:

“Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice. Justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love.”

—The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.

The enduring lineage of collective liberation demonstrates that the purpose of power is not domination, but the cultivation of humane relationships and life-affirming ecosystems—which Dr. King called The Beloved Community:

“I do not think of political power as an end. Neither do I think of economic power as an end. They are ingredients in the objective that we seek in life. And I think that end or that objective is a truly brotherly society, the creation of The Beloved Community.”

—King, cited by The King Center, from Christian Century Magazine (July 13, 1966)

The Beloved Community was first coined in the early 1900s by philosopher-theologian Josiah Royce, who founded the Fellowship of Reconciliation. The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (a member of the Fellowship of Reconciliation) popularized the term and imbued it with a deeper meaning.

As early as 1956, Dr. King spoke of The Beloved Community as the end goal of nonviolent boycotts. At a victory rally following a favorable U.S. Supreme Court decision in Browder v. Gayle (which desegregated Montgomery buses), King said:

“We must remember as we boycott, that a boycott is not an end within itself; it is merely a means to awaken a sense of shame within the oppressor and challenge his false sense of superiority. But the end is reconciliation; the end is redemption; the end is the creation of The Beloved Community. It is this type of spirit and this type of love that can transform opposers into friends. It is this type of understanding goodwill that will transform the deep gloom of the old age into the exuberant gladness of the new age. It is this love which will bring about miracles in the hearts of men.”

—King, “Facing the Challenge of a New Age,” Address Delivered at the First Annual Institute on Nonviolence and Social Change (1956)

In the following year, he expanded upon this vision in another context:

“The aftermath of nonviolence is the creation of The Beloved Community. The aftermath of nonviolence is redemption. The aftermath of nonviolence is reconciliation. The aftermath of violence is emptiness and bitterness… Let us fight passionately and unrelentingly for the goals of justice and peace. But let’s be sure that our hands are clean in this struggle. Let us never fight with falsehood and violence and hate and malice, but always fight with love, so that when the day comes that the walls of segregation have completely crumbled in Montgomery, that we will be able to live with people as their brothers and sisters.”

—King, “The Birth of a New Nation,” Sermon Delivered at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church (1957)

Dr. King envisioned The Beloved Community as an attainable goal achieved when a critical mass understood and committed to the practice of nonviolence. It invites us all to recognize our roles in helping assemble that critical mass. It calls us to use our power to shift loveless systems toward honoring human dignity so all can share in the wealth of our planet with reverence. It teaches us to transform prejudice, bigotry, and supremacy into an all-inclusive spirit of togetherness. It enables us to address disputes through conflict resolution and reconciliation. It beckons us to become people who love peace and justice more than war and violence. It insists that love and trust prevail over fear and hate.

While hate has been a unifying force for some, it pales in comparison to the power of love in action. Instead of waiting to see whether the revolution is televised, let’s remember the revolution is relational. May we, the people, continue becoming The Beloved Community through committed practice.

It is time to update our vision for justice as collective liberation—to advance it by practicing nonviolence, to steward it by embodying agapē, and to cultivate it by building The Beloved Community.

“Justice is what love looks like in public.” It’s love bearing truth. It dismantles lies that uphold oppression and lays the foundation for collective liberation.

Cruel, loveless systems are clearly unsustainable. Transition is inevitable. Let’s choose a just transition. May the enduring courage and steadfast commitment of our love-centered predecessors strengthen us to improve conditions for present and future generations.

*Editorial note: This post was originally published in January 2025 and has since been updated to clarify key ideas, include additional sources, and reflect a present-day perspective.

Acknowledgments

Dr. King’s achievements were not his alone. His wife, Mrs. Coretta Scott King, significantly influenced this work and organized for economic justice, social equity, and global peace. Together, they contributed to the movements of their time among fellow revolutionaries, including Albert Luthuli, Amelia Boynton Robinson, Andrew Young, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Benjamin Mays, Bernard Lee, Clarence Jones, C. T. Vivian, Diane Nash, Dorothy Cotton, Ella Baker, Howard Thurman, James Baldwin, James Bevel, James Farmer, Jo Ann Robinson, Joseph Lowery, Fannie Lou Hamer, Fred Shuttlesworth, Gloria Richardson, John Lewis, Kwame Nkrumah, Kwame Ture, Mahalia Jackson, Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, Nnamdi Azikiwe, Prathia Hall, Ralph Abernathy, Rosa Parks, Roy Wilkins, Thich Nhat Hanh, Whitney Young, and many more. Their combined efforts brought forth pivotal systemic change, catalyzed momentum toward a just future, and paved tremendous ground for movements today.

Please note that the orange text throughout this post are hyperlinks to sources with more information. The author of this post recommends exploring those links and visiting The King Center, which embraces the conviction that The Beloved Community can be achieved through an unshakable commitment to nonviolence. Established in 1968 by Mrs. Coretta Scott King, The Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change (The King Center) is a global destination, resource center, and community institution.

“Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.”

—King, “I Have a Dream,” March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (August 28, 1963)